Helo Pawb

On Wednesday I drove to Cheshire to hear a talk by the man once described by The Independent as ‘The most important author working in the UK’. The title of the talk was ‘Powsels and Thrums: The Loom of Creation’. The setting was The Wolfson Auditorium, at Jodrell Bank, the site of the Lovell Radio Telescope. The author was Alan Garner, who lives at Blackden, a 15th century timber-framed house just three fields over from Jodrell Bank. He moved into the house he calls ‘Toad Hall’ in the same year the telescope was established.

|

| The Lovell Radio Telescope at Jodrell Bank |

I first encountered Garner years ago when, as an adult, I read The Weirdstone of Brisingamen, his first novel, published in 1960 when he was 25. I don’t remember much about the book, probably because I was in my Tolkien phase, though others I know, who came to it when they were teenagers, were so enthralled by the story they re-read it a number of times.

|

| The edition I first read |

Then I journeyed to Britain in 2013 to attend a conference in Oxford and to conduct research for my dark ages novel. One of the people at the conference, when he heard about my novel, suggested I come and stay with him in Manchester so he could show me Alderley Edge, which had a Merlin legend associated with it. This legend figured heavily in Weirdstone, and so I became interested in reading more by the author. I spent much of last year reading all Garner’s novels and anything else of his I could find, and was blown away by his writing: his stunning use of language, including Cheshire dialect, his evocation of the Cheshire landscape, and his weaving of the everyday and the mythic, what I have come to call ‘mythic realism’. So, when I found out he was giving this talk, the last he will ever deliver, on a date I happened to be back in the country, I endured the six-hour round trip to hear it.

|

Alderley Edge: One of the candidates for the Black Gates,

behind which the Sleeping King and his Knights might be found |

An Attempt at a Glossary of Cheshire Words defines ‘Powsels and thrums’ as ‘dirty scraps and rags’. Garner’s definition, however, took on the personal: what a weaver ancestor of his would refer to as the off-cuts and discards of materials used for the weaving or having come from the woven materials themselves. For Garner, the phrase becomes an image used to express his understanding of creativity: ‘the bringing together of disparate things and combining these in new ways’. Art ‘makes connections between entities that have not been seen before’.

|

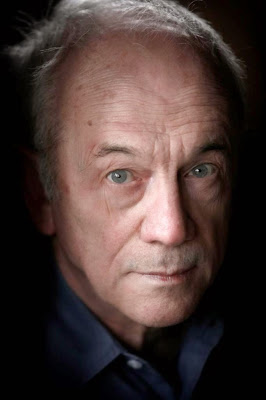

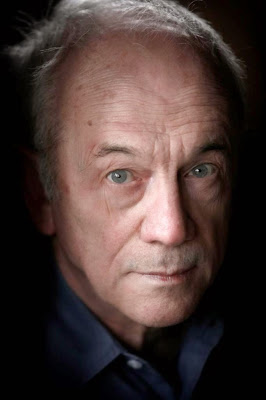

Alan Garner, photo by Gary Carlton

from the Jodrell Bank website |

Garner is a brilliant speaker: witty, sarcastic, poignant, stimulating and provocative. He is a storyteller trying to evoke for his audience the way of creativity, not an academic dissecting and analysing the psychology of creativity or the meaning of creative works. He uses stories, anecdotes, quotations from other writers (mainly Dylan Thomas, from that poet’s Introduction to his Collected Poems) and song (a rendition of a Danny Kaye song from a childhood experience at church). He also uses props: an ancient stone handaxe and a bronze age polished axe head he once put on Sir Bernard Lovell’s desk to emphasis his point that the telescope started with it, an early artefact of ‘the questing ape’.

One story, which illustrates his idea that ‘Artists magnify the land…through intensity of vision’, was of a bricklayer he once observed making a wall. When the man had finished, he stood back, studied his work, and tore the wall down. When Garner asked him why he had done this, the man replied that the lower course of bricks was ‘half a brick out’. This course was below ground level. ‘But no one would see that,’ Garner said. ‘I would,’ the bricklayer replied. Intensified vision, even in the everyday work of craftspeople who exemplify the two precepts Garner’s grandfather, a smith, gave him and that Garner has lived by as a writer ever since:

One was always take as long as the job tells you to take, because the job will be there when you are not, and you don't want people to say, what fool did that? So I'm a very slow worker. The other precept was if the other chap can do the job, let him. In other words, do only what is uniquely yours. (‘Interview with Alan Garner’, Raymond H Thompson, The Camelot Project, 1999)

And, yes, Garner is a slow worker. He spent seven years writing Red Shift, which recounts 1,000 years of events through three intersecting narratives, and 12 years writing Strandloper (which some consider his masterpiece), a book about William Buckley, who came from the Cheshire region Garner celebrates in his work and who spent 32 years with aborigines after being transported to Australia. Much of his writing time is taken up with research and the actual crafting of language and incident.

As an example of this process, for his book Elidor: ‘I had to read extensively textbooks on physics, Celtic symbolism, unicorns, medieval watermarks (and) megalithic archaeology…’ (Times Literary Supplement, 1968, quoted in ‘Wild Magic: Alan Garner’, Fabulous Realms website).

But back to the talk. Here are some other gems (scribbled down in my notebook in the dark of the auditorium):

- Creativity is risk, play and intuition.

- Creativity is not a job, but a state of being…in service to something else.

- Art makes people feel.

- Intelligence observes immensities [as in the observations of the radio telescope at Jodrell Bank], and imagery [the work of art] translates the observations so they provide emotional understanding.

- Imagery/art informs science, and the reverse.

- Creativity is prayer…and prayer is a dialogue with the numinous.

After the talk, I lined up for his signature on my new copy of his latest and last book, Boneland, the novel that completes the story began in his first two books, The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and The Moon of Gomrath. While these first two novels might be seen as YA fantasies (though Garner has always said he never writes for children), this last work, as with the novels since Red Shift, is adult and mythic. These later books may be difficult, ‘reader-unfriendly’ one critic asserted in a review of Thursbitch, but the joys of language and the rendition of the numinous await those who persevere.

After gaining the signature and chatting briefly with his wife, Griselda, about ‘the Australian book’, I drove back, with care, to Corris in my own ‘mythic realism’ experience—late at night, through mountains on a winding road, in rain that formed a tunnel in the headlights, and with temperatures just above zero—eager for the warmth of my studio and another encounter with Alan Garner’s rich, evocative, resonant writing.

By the way, I overheard someone say the talk will be published in one of the UK newspapers. When I find out more details, I’ll let you know.*

Until next time.

Pob Hwyl

Earl

(* The lecture can be found here.)