Haia Pawb

Part of my dark ages novel occurs on Anglesey (Ynys Môn), so I spent almost a week on the island researching megalithic tombs, Iron Age villages (both ruins and reconstructions), and other possible settings. On my first day, I checked out two of these: Bryn Celli Ddu and Moel-y-don.

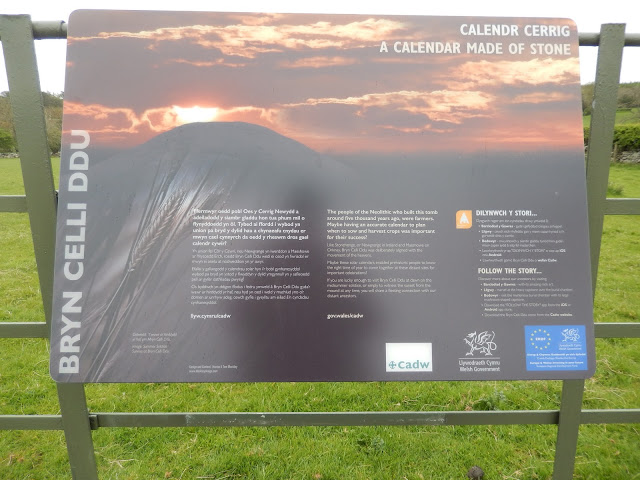

After visiting Bryn Celli Ddu (The Mound of the Dark Grove) in 2013 and being impressed by the rounded stone pillar inside the central chamber—a raw occurrence, apparently—I decided to use the tomb for an important early scene in the novel. This new visit was a chance to explore the tomb in more detail than the last.

The tomb is located a few miles southeast of Llandaniel Fab. Although the history of the site goes back to 3,000 BC, with the building of a henge and ditch, for my purposes I was interested in the tomb itself, which was built roughly 2,000 BC and would have remained in its original state till it was explored in the early 20th century. (After excavation, the mound was rebuilt, but only to about a quarter of its original size.)

Features I found of interest included

- The entrance, which is aligned to the summer solstice. The passageway is over 20 feet long and has a low shelf, which might have been used for storing cremated bones, on the right side as you come in.

- The stone pillar, as mentioned, which stands over six feet tall and is freestanding, meaning it doesn’t have a structural function but possibly a ceremonial one. The pillar has some markings on it, which some sources claim represent important astronomical events. However, given light doesn’t reach the pillar through the passageway (only through the rear opening, which is not an original feature), I don’t feel this assessment is correct.

- The sprinkling of offerings (feathers, flowers, crystals, candles, shells, bundles of twigs and material) on shelves around the chamber. This is a recent activity, as I saw nothing of this at my last visit.

- The ‘Pattern Stone’, with its serpentine wave and spiral shapes, which was found buried near the centre of the mound, which itself had a stone slab with an ear bone beneath it. The original slab is now in the National Museum of Wales, but a replica has been set upright outside the southwest side of the mound, a spot felt to be its placement before the original henge was destroyed to make way for the chamber tomb.

As for the chamber itself, it has a packed dirt floor and walls formed from six massive slabs of rock, with pebbles and small rocks filling crevices between these and between the walls and the two slabs used for the roof. The chamber is tall enough to stand in, but one needs to duck when traversing the long passageway.

After pacing out the dimensions of the chamber, I spreading my jacket on the floor and spent a long while soaking in the atmosphere and imagining how my important scene would play out. Luckily, no other visitors interrupted my meditations. When I was happy with my explorations inside the mound, I went outside to survey the undulating landscape and a distant long, flat-topped hill and again imagine what it might have looked like in the sixth century. Flights of rooks above woods thick with underbrush probably extending right to the tomb. Sounds of animals foraging and hunting. A fox skirting an open field in which a few long-horned cattle from the nearby settlement graze. A chiming brook whittling its way through soft, rich earth.

I then jumped into my hire car and drove through Llanfairpwll towards the Menai Strait (Afon Menai), which separates Ynys Môn from the mainland of Wales. I was investigating Moel-y-don, a possible site for the Roman invasion of Ynys Môn c. 61AD.

Another early scene in the novel is a vision of this brutal battle when the Romans crossed the straight with cavalry and flat-bottomed boats carrying infantry. The only known description of the battle is given by the Roman Historian Tacitus in his Annals XIV:

He [Suetonius Paulinus] prepared accordingly to attack the island of Mona, which had a considerable population of its own, while serving as a haven for refugees; and, in view of the shallow and variable channel, constructed a flotilla of boats with flat bottoms. By this method the infantry crossed; the cavalry, who followed, did so by fording or, in deeper water, by swimming at the side of their horses.

On the beach stood the adverse array, a serried mass of arms and men, with women flitting between the ranks. In the style of Furies, in robes of deathly black and with dishevelled hair, they brandished their torches; while a circle of Druids, lifting their hands to heaven and showering imprecations, struck the troops with such an awe at the extraordinary spectacle that, as though their limbs were paralysed, they exposed their bodies to wounds without an attempt at movement. Then, reassured by their general, and inciting each other never to flinch before a band of females and fanatics, they charged behind the standards, cut down all who met them, and enveloped the enemy in his own flames.

The next step was to install a garrison among the conquered population, and to demolish the groves consecrated to their savage cults: for they considered it a pious duty to slake the altars with captive blood and to consult their deities by means of human entrails. While he was thus occupied, the sudden revolt of the province was announced to Suetonius.

That the island, with its sacred groves, was the centre of Druid religion in Britain is commemorated by one of the ancient poetical names for Anglesey: the Old Welsh Ynys Dywyll (‘Shady Isle’ or ‘Dark Isle’). The sudden revolt, of course, was the one by Queen Boudica.

I arrived at the shoreline in drizzly weather. Strips of seaweed on a beach on shells and pebbles. Seagulls wheeling overhead. Mud and sand lining the beach and stretching around the point, which seems to align with a nob of land sticking out from the opposite shore. The distance across the strait, about 500 yards, seems short enough for the use of onagers and the crossing by boat and horse.

After again taking time to absorb the scene and imagine the battle itself, and with the drizzle turning into lashing rain, I returned to the car and drove back to my hotel.

So, at the end of day one on Ynys Mon I had explored two important sites for my novel. A successful day of research.

All comments are welcome.

Cofion cynnes

Earl